Crits Del Mur

From October 3rd to December 1st, 2024.

Llotja de Sant Jordi, Alcoi

From October 3rd to December 1st, 2024.

Llotja de Sant Jordi, Alcoi

THOUGHTS ON THE NATURAL EVOLUTION OF URBAN ART AND GRAFFITI

We assume that primitive humans were unaware of the fact that they were creating art. In the rock shelters of La Sarga, thousands of years ago, humans painted their lived reality's impact on them. These were large, thickly drawn red macro-schematic figures representing people and animals. For archaeologists, these paintings are a major breakthrough in research. So much so that "a cry of emotion preceded the discovery," as expressed by Camil Visedo Moltó, the first director of the Municipal Archaeological Museum of Alcoi.

Significant expressions on walls have also been discovered in the Roman city of Pompeii, buried under volcanic lava. Inside and outside homes, drawings, phrases, names, and signatures (tags) were found—a repertoire of love declarations, erotic and sexual texts, political writings, and commercial announcements. These represent a fascinating testament to urban life at the time, showcasing how inhabitants wrote to either define their territory or leave a mark of their presence in the world.

Joan Fuster recounts in The Discredit of Reality how the art of painting began to revive in a small village near Florence called Vespignano, where a marvelous child prodigy was born. This child, who could draw a sheep from nature, astonished Cimabue, who was traveling to Bologna and saw the boy sketching sheep on a stone. That boy would become his apprentice, Giotto. Once again, a drawing on stone.

In 1930, Diego Rivera painted a mural featuring Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky in New York's Rockefeller Center—right in the heart of capitalism. The mural was immediately destroyed, but the painter reproduced it at the National Palace in Mexico. Art has always been used by politics and power, just as artists have sought to raise awareness and provoke social change, inviting reflection on abuse and injustice. Similarly, abstract painting in New York became a powerful tool to counter Soviet propaganda—art without a message, leading to abstract expressionism by artists like Pollock and Rothko, among others.

We assume that primitive humans were unaware of the fact that they were creating art. In the rock shelters of La Sarga, thousands of years ago, humans painted their lived reality's impact on them. These were large, thickly drawn red macro-schematic figures representing people and animals. For archaeologists, these paintings are a major breakthrough in research. So much so that "a cry of emotion preceded the discovery," as expressed by Camil Visedo Moltó, the first director of the Municipal Archaeological Museum of Alcoi.

Significant expressions on walls have also been discovered in the Roman city of Pompeii, buried under volcanic lava. Inside and outside homes, drawings, phrases, names, and signatures (tags) were found—a repertoire of love declarations, erotic and sexual texts, political writings, and commercial announcements. These represent a fascinating testament to urban life at the time, showcasing how inhabitants wrote to either define their territory or leave a mark of their presence in the world.

Joan Fuster recounts in The Discredit of Reality how the art of painting began to revive in a small village near Florence called Vespignano, where a marvelous child prodigy was born. This child, who could draw a sheep from nature, astonished Cimabue, who was traveling to Bologna and saw the boy sketching sheep on a stone. That boy would become his apprentice, Giotto. Once again, a drawing on stone.

In 1930, Diego Rivera painted a mural featuring Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky in New York's Rockefeller Center—right in the heart of capitalism. The mural was immediately destroyed, but the painter reproduced it at the National Palace in Mexico. Art has always been used by politics and power, just as artists have sought to raise awareness and provoke social change, inviting reflection on abuse and injustice. Similarly, abstract painting in New York became a powerful tool to counter Soviet propaganda—art without a message, leading to abstract expressionism by artists like Pollock and Rothko, among others.

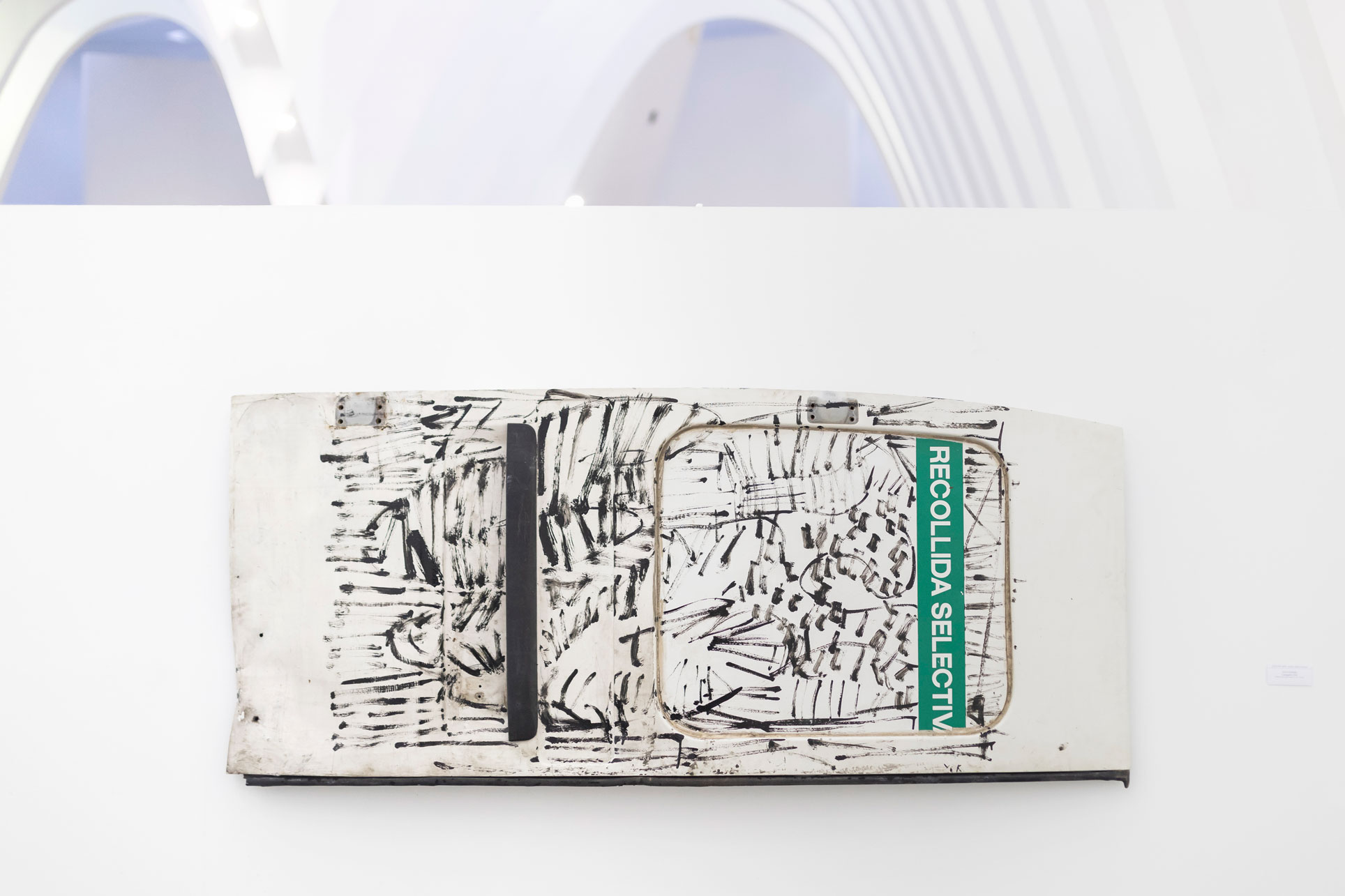

Berger taught us to look at artworks and paintings. Similarly, street art has always existed due to the human need to express personal or collective emotions. In the 1980s, the art market introduced graffiti into the artistic sphere in the form of paintings or graphic works. These reflected the personal and psycho-evolutionary need of their creators, yet remained tied to graffiti’s free and revolutionary street spirit. This transformation became known as Aerosol Art or Gallery Graffiti. Galleries, museums, and art spaces amplified this new movement. In Spain, the arrival of New York graffiti at ARCO in 1985 made a powerful impact with works by renowned artist-writers such as Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lady Pink, and TOXIC. Their presence at the fair opened doors for local artists in subsequent editions.

In Alcoi, mural painting emerged in the 1980s as a means to denounce injustices like waste, consumerism, genocide, or Pinochet’s 1973 coup in Chile. Later, the graffiti revolution reached the streets, becoming a hallmark of identity. As in other places, a network of connections between local and regional artists formed, driving the evolution and expansion of this socio-cultural phenomenon.

The ephemeral nature of this practice means that many once-active areas have disappeared over time. Nevertheless, the natural evolution of the graffiti movement has continued to develop, encompassing both street art and urban art. The Urban Skills festival in Alcoi has arguably reignited this artistic practice. Held annually for the past five years, the festival hosts urban artists from national and international scenes. The magnitude of the project transforms the city’s neighborhoods into an open-air museum, turning the streets into a space for communication and art.

Text by Maria Guillem

Art Historian

Curator of the Exhibition

The participating artists are:

Vincent C.V.D. Spek (Kaniz), Xavi Ceerre, Lluïsa Penella, Germán Bel (Fasim), Javier Pérez (Roice 183), and Stillo Noir (Tanya Heidrich).

Exhibition texts by:

Maria Guillem and Oscar García.

In Alcoi, mural painting emerged in the 1980s as a means to denounce injustices like waste, consumerism, genocide, or Pinochet’s 1973 coup in Chile. Later, the graffiti revolution reached the streets, becoming a hallmark of identity. As in other places, a network of connections between local and regional artists formed, driving the evolution and expansion of this socio-cultural phenomenon.

The ephemeral nature of this practice means that many once-active areas have disappeared over time. Nevertheless, the natural evolution of the graffiti movement has continued to develop, encompassing both street art and urban art. The Urban Skills festival in Alcoi has arguably reignited this artistic practice. Held annually for the past five years, the festival hosts urban artists from national and international scenes. The magnitude of the project transforms the city’s neighborhoods into an open-air museum, turning the streets into a space for communication and art.

Text by Maria Guillem

Art Historian

Curator of the Exhibition

The participating artists are:

Vincent C.V.D. Spek (Kaniz), Xavi Ceerre, Lluïsa Penella, Germán Bel (Fasim), Javier Pérez (Roice 183), and Stillo Noir (Tanya Heidrich).

Exhibition texts by:

Maria Guillem and Oscar García.

PREV